Think back to September last year. What happened early that month? What news shook the world and reverberated for weeks, if not months?

That’s a question I’ve been asking friends and colleagues lately.

On September 8, 2022, at 6.30pm in Britain, Buckingham Palace announced the death of Queen Elizabeth II. The news broke just 30 minutes before the press embargo lifted on a major review of climate change tipping points in the journal Science.

The paper in Science was truly earth-shattering, as it heralded changes that could threaten the future of civil society on this planet. But it was the other news that captured the world’s attention.

So, in case you missed it, I’d like to alert you to this important paper by British climate researcher David Armstrong MᶜKay and colleagues.

Grappling with tipping points

The question of when global warming might push elements of the climate system past points of no return has come into focus over last the decade or so. And tipping points once thought to be far off in the distance have come into sharp relief.

The research examines major features of the global climate system, such as ice sheets, glaciers, rainforests and coral reefs. It asks when melting of ice sheets on Greenland and West Antarctica would become irreversible, ultimately contributing many metres to sea level. Or when thawing of frozen ground in the Arctic might start producing so much methane and carbon dioxide (CO₂) that it blows the global emissions budget.

Amazonian forest die-back is another major part of the Earth’s climate system. Global heating and regional reductions in rainfall could cause trees to die, releasing large amounts of greenhouse gases. Fewer trees ultimately means less rainfall for those that remain, creating a vicious cycle.

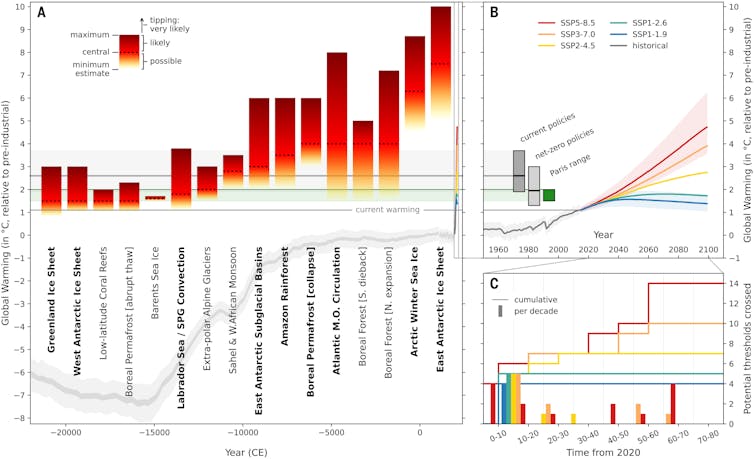

The pivotal paper in Science reviewed more than 220 papers published since 2008 to estimate what level of global temperature rise (relative to pre-industrial levels) would trigger each of the global and regional climate tipping points.

The world has already warmed 1.1℃ (see the horizontal line “current warming” in the chart above). The 1.5℃ and 2℃ lines represent the Paris Agreement on climate change targets agreed to internationally in 2016.

Once initiated, irreversible melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet would add about 5m to global sea level. Disturbingly, the threshold for this tipping point may have already been crossed. If not, it is “very likely” to be crossed at 2℃.

Ice sheets in West Antarctica contain about another 3.5m of sea level rise, and again, irreversible melting is likely to begin at around 2℃.

So, that’s about 5m from Greenland and another 3.5m from West Antarctica. Add thermal expansion from warming oceans, and mountain glacier melt, and we have more than 10m of sea level rise to contend with.

While that will unfold over many centuries, it will be irreversible and inexorable. It means children born today will likely see sea levels rise by well over 1m early in the 22nd century. Longer-term, these changes will shape the planet for the next 150,000 years or so, until the next ice age.

Much of the world’s tropical coral reefs will likely die at 1.5℃ to 2℃ of warming. And thawing of Arctic permafrost would start releasing vast amounts of greenhouse gases, equal to about 10% of human emissions. That would likely push global temperature up by another 0.5℃ to 1.0℃ (on top of 2℃).

Thankfully, logging and wildfire aside, the Amazon forest looks relatively safe until about 3℃ of warming. But the combination of some of those other tipping points might get us there, setting off a further cascade of tipping points.

Can we avoid disaster?

After decades of delay, our chances of keeping global warming below 1.5℃ are pretty slim. But, clearly, this research shows that limiting warming to 2℃ will not keep us safe.

The focus on “net zero by 2050” has in fact done us a disservice. If we let emissions remain anywhere near current levels for much longer, by 2030 we will have used up the carbon emissions budget that would allow us to stay near 1.5℃.

We need to act quickly and at least halve current emissions by 2030 on the way to net zero before 2050. This research shows that failing to do so will trigger 10m or more of sea level rise. That will gradually displace hundreds of millions of people and many of the world’s major cities.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has begun talking about the possible failure of civil society in response to increasing extreme events. We are seeing early indicators of this in Australia, with people living in tents for years after floods made worse by climate change. They face decisions about whether or not to rebuild on that land.

How long will there be money available to provide disaster relief in Australia and around the world? Where will hundreds of millions of people go after being displaced by extreme wet bulb temperature, crop failure, fire, flooding and sea level rise?

How did we get here?

Arriving at this juncture in human history feels like a massive failure. A failure of leadership, of decision making, of information dissemination through media, and perhaps our priorities, has left us in this extremely challenging position.

Many factors have conspired against us. These include fossil fuel companies funding misinformation and climate-related “green washing” – exaggerating or misrepresenting their climate credentials. Elected leaders being influenced by donations from the fossil fuel industry. Earlier low-resolution climate models failing to capture local scale processes, and therefore underestimating climate system sensitivity. Poor media communication of the urgency of the issue. And throw in some good old human “optimism bias” towards positive outcomes.

As a climate scientist, with almost 18 years experience in operations at the Bureau of Meteorology and more recently, in my work on high resolution climate projections for state government, I deeply know the climate grief so eloquently communicated by climate researcher Joelle Gergis.

In response, I have had to draw on tools such as meditation and mindfulness to deal with the awareness the science presents including the likely future suffering of so many. It is challenging to see where we are heading and – with what is at stake – to see life going on as if everything is fine.

A turning point

Future events are going to challenge us in many ways. Humanity faces a choice between retreat into fear and war, or cooperation and collaboration. There is much already happening and a lot we can do, as individuals and communities. We can restore landscapes, reward sustainability, create a circular economy and electrify everything. But we need to act fast.

So, as King Charles III’s coronation plays across our TV screens and media feeds in coming days, keep the incredibly urgent climate crisis in mind. Ask our leaders to step up. Do not be distracted, as future generations will judge us for the choices we make today.

Darren Ray, PhD candidate | Paleoclimate, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.